Interviews

Ingo Niermann in an interview with Leonore Mau (2005)

Ingo Niermann (IN): What brought you to photography?

Leonore Mau (LM): Every person’s life develops in some direction. Life holds all kinds of accidents in store. How did two people who married get to know each other? There are so many absurd stories. Like a friend of mine who left the house one evening in the pouring rain to post a letter and from the opposite direction a man with an umbrella approached the letterbox, also with a letter in hand. In that moment – he became her husband. Likewise: how do you end up with your profession?

After doing my Abitur I went to art school, but with our flight from Leipzig to here in Hamburg in ’45 we were left with nothing, absolutely nothing. It takes years before you can lead a normal life again. As a refugee you are a second-class citizen until you suddenly shift up to become first class again because you are doing something that’s successful.

It all came down to me managing to get a camera, a Leica, and what I actually wanted was… but why am saying all this? I am a photographer, period.

IN: And did you immediately realise: this is now my profession?

LM: Yes, I was never a casual kind of photographer. Once I’d got the camera in Hamburg and started using it, with the very first film I shot I produced the cover photo for a Hamburg harbour magazine. It took off right away. Even though I took very few photos of Hamburg.

IN: Hamburg didn’t interest you much?

LM: There are plenty of fantastic photos of Hamburg, it’s enough when other people do that.

IN: You then started photographing houses for architecture magazines.

LM: I was once asked by an editor if I also photograph architecture? And since back then I was still married to an architect and knew a bit about it, I started doing this and earned good money with it, which I urgently needed in order to buy really good camera equipment.

IN: After moving in with the author Hubert Fichte in the early ’60s what was your first joint project?

LM: We made photo films for German television. First here in Hamburg – Der Tag eines unständigen Hafenarbeiters. Then in Sesimbra in Portugal. Actually, the reason we went there was because we loved the sound of its name. It used to be a very beautiful fishing village by the sea, but being so close to Lisbon it has now turned into a tourist hotspot. In the middle of the village there was a fish market, and in fact all I photographed was fish. For a 20-minute film you need about 500 or 600 photos. That’s a lot, but I absolutely loved doing this work. Hubert Fichte then selected them, decided on their sequence and how long each image should last: he edited the film.

Then I made another photo film in Rome on the Spanish Steps. They were always crowded with young people, then at the top was this elegant hotel from where elegant people descended. For the whole time we were at the Villa Massimo, that was where I went.

Sadly, photo film as a medium is no longer particularly en vogue. Otherwise I could compile a photo film, for instance, from all my documentary material on African-American religions.

IN: Your research into African-American religions started in 1968 with a journey to Brazil. How did this trip come about?

LM: For a start, we had enough money at the time.

IN: Hubert Fichte had just published his novel Die Palette.

LM: Yes, and he had earned quite a bit of money with it. Then we bought our tickets, first for a short trip – three months, which is not so long.

IN: And what made you decide on Brazil?

LM: Because we knew that the most beautiful rites took place in Brazil – those of Candomblé – and because we could speak Portuguese.

We would pass through a favela at night, always following the drumming. Wherever it sounded the loudest and most beautiful, we’d stop in front of a hut. But we didn’t go inside; instead, we just waited. The people have a sixth sense – or seventh or eighth – and after a couple of minutes two of them came out and asked us what we were looking for. Since we answered in Portuguese, they were instantly well disposed towards us and invited us to come inside. I asked them if I could also take some photographs. They then talked among themselves for a while without realising that we perfectly understood what they were saying. What they said was, “Here are two people from Europe and the woman wants to take photos. But there’s no harm in it since the gods won’t allow it, so nothing will appear in the photos.” But the gods allowed it after all; it was all there on film.

After our three months were up, we decided to raise money to return for a full year because the most important festivals happen throughout the year. And we photographed all of them.

IN: The interest in African-American religions not only led you to Africa. But on your trip to the Royal Court of Abomey in Benin you also brought a message from the priestesses of the Brazilian temple Casa das Minas, which is said to have been founded 300 years before by an enslaved daughter of the King of Abomey.

LM: Everyone in Brazil knows what the Casa das Minas is. The priestesses are held in great esteem. We told them we were travelling to West Africa and they gave us a message and a tape with a recording of their singing to take to the Royal Court of Abomey. As a mark of his ambassadorship, Hubert Fichte received a colourful glass bead necklace. Each colour and the respective positions of the glass beads to one other represent something in particular.

At the Royal Court, once they’d inspected the necklace and listened to the singing on the tape, they took a large sheet of paper and wrote an invitation to the priestesses of Casa das Minas.

IN: Did they understand the Brazilian singing and the necklace?

LM: Yes, they were deeply impressed and moved.

IN: Did the priestesses take up the invitation?

LM: I don’t think so. Somehow or other we would have heard about it. The priestesses of the Casa das Minas told us that they would have to go to Abomey one day because something was missing in one of their rites. So Hubert Fichte said, “We’d better start right away. Twice a week, we’ll study French.” Hubert began teaching them French and it was all going very well, but then he died.

Later, the priestesses sent me a message via someone who was coming to Germany to say that the Casa das Minas wished the necklace to be returned. Just imagine how people here in Germany reacted when I told them about this: What, some old string of glass beads? You must be nuts. – No, it’s a very special glass bead necklace and I don’t want to discuss it with you anymore. I flew to Brazil and brought the necklace back to them. They were so thrilled, it was lovely.

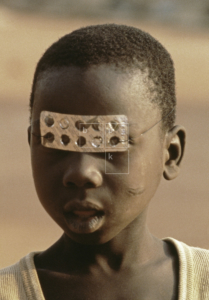

IN: At the Royal Court of Abomey you also took the fascinating and disturbing picture of a young boy wearing an empty blister pack of pills as a mask.

LM: We were standing on the street looking around us. Suddenly I saw the boy standing there. Without any explanation I told Hubert Fichte, I’ll be back in a moment – because I was afraid the boy might run away. I asked him to stand still because I wanted to take his picture – which thrilled him.

Children in West Africa are unbelievably skilled in imitating things from found rubbish or simple materials. Recently there was a film about Senegal where confecting imitation toys has become a veritable industry.

IN: Have you never taken a picture without asking first?

LM: No, I’ve always kept to the rule I set myself never to become the unsolicited photographer who collects people. In fact I’ve always asked first, at ceremonies too. Whenever we heard that there was a temple somewhere or other, we first went there without a camera, introduced ourselves and asked if we could participate. And when they agreed, we stayed through to the end. Not shyly, just snatching a glimpse the way tourists do, but sometimes really for twelve hours at a time.

Hubert was a genius at scouting things out. And he always got what he wanted – it was amazing, he had such an aura. We were refused just once: but that was understandable because it was a secret ceremony. Otherwise it always worked out.

IN: There’s a description by Hubert Fichte in his book Petersilie: “A boy has strapped on an airplane, blood-smeared metal, mirror shards. He’d bound bulging lips studded with boars’ tusks to his face, which he took off when Leonore wanted to photograph him.”

LM: That could very well be because there is a superstition – very strong in Islamic countries – and you have to be very careful because they believe you’re taking their identity away from them. I never insisted, never said, “But I want this, do this for me”. I never ran into difficulties because this is something I always respected. But on the other hand, there were also times when I turned up without my camera and someone would ask, “Where is Kodak?”

IN: Did it ever happen that someone was willing to let you photograph, but it still struck you as indiscreet?

LM: The line between indiscretion and fascination is very, very thin. In Brazil once, there was catastrophic flooding caused by rain. It poured for days on end and all the favelas slid down the mountain, and for days we couldn’t get out of the little house we’d rented because it was surrounded by water.

When I finally managed to get out and head towards the centre of the city with my camera, there were dead bodies in the streets, completely swamped in mud. I was about to photograph them when the police saw me with my professional equipment – and they immediately tore off the sheets covering the dead. They practically challenged me, with friendly gestures, to take a picture. And I did as well – it is featured, very small, in the photo book Xango, along with this story.

IN: In West Africa, in the ’70s, you shot photos of the mentally ill who were being held in public places. Didn’t they feel as if they were on display?

LM: On the contrary. They were excited to have so much attention being paid to them. No problem at all. That was in Togo or Benin. The people who – as is said – aren’t normal, they weren’t put in clinics, but instead staked out on the public squares. That way, they’re still part of the community; people talk with them. Children especially like talking to them and they like talking to children. Of course, sometimes people also laugh at them, but they’re never treated badly. That’s what we honestly observed, we spent a whole day in such a village. No aggression.

Of course, it is horrible too, but they don’t have any money for a hospital. And ultimately, when you think about it, you can be declared insane by society – it happens very quickly – and then you are lying there all day long, more or less looking at nothing but white walls. That’s a perfect recipe for going mad.

In Africa they also have completely different explanations for mental illness; for example, bad treatment of dead family members. If you don’t honour them properly. If someone breaks society’s rules, it doesn’t mean he is immediately cast out. You’d really have to be stark raving mad before they say: he is ill.

IN: How did you first get involved with mental illness and psychiatry in West Africa?

LM: In Senegal, there were many intellectuals we spoke to who told us about the famous psychiatric school in Fann and accompanied us there as well. We spent three weeks there in 1974. Very nearby was a small, respectable hotel. Without knowing about it beforehand, this too was where we experienced an amazing solar eclipse. The employees in the hotel were trembling with fear – they had the feeling that everything had come to an end, the end of the world, the end of life. That was quite formidable.

Fann was run by the French professor Henri Collomb. We also flew with him in his small plane to Casamance, to the psychiatric village there he founded. The village was constructed in such a way that the sick could live together with members of their family. They had their own little straw huts and could cook there as well.

Once a week, the doctors would meet with a patient and his family for a pinth, which in Wolof means “get-together”. The case would then be discussed, but most of the doctors only spoke the colonial language, French. Only one of them was able to speak Wolof because his wife was Senegalese. Hubert Fichte wrote about this in his text, Gott ist ein Mathematiker (God is a Mathematician). If you can’t speak to someone declared mentally ill in his own language, that’s insanity to the third degree.

Untitled (Launches in the Port of Hamburg), 1966

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Ohne Titel (Maison Jaoul), 1960

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (Fish market by the sea), 1964

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (On the Spanish Steps), 1967/68

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (Priestesses of the Casa das Minas Temple), 1981/82

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

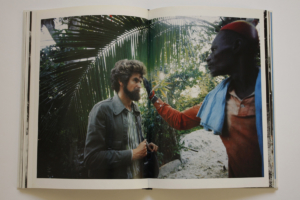

Untitled (Hubert Fichte at the 106-year-old

King of Abomey), 1975

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (African Boy with Blister Mask), 1975

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

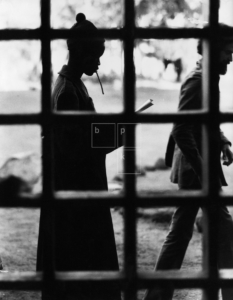

Ohne Titel (Hubert Fichte in psychiatry

in Fann), 1976

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (Hubert Fichte in Trinidad), 1974

In the picture book Hälfte des Lebens. Leonore Mau:

Hubert Fichte. Eine fotographische Elegie

von Ronald Kay

© Nathalie David

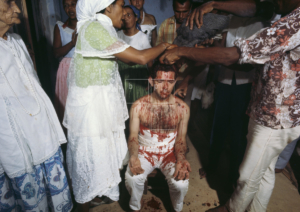

Untitled (The bloodbath), 1971

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Fahrt nach Karlsruhe, 1965

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Hubert Fichte

The picture book Psyche

© Nathalie David

Fata Morgana, c. 2002

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Nathalie David in an Interview with Leonore Mau (April 2006)

Excerpt from the interview. Conducted in Dürerstraße 9 in the Othmarschen of Hamburg.

Leonore Mau (LM): We wanted to go to Brazil, that had always been our dream but the travel was simply very expensive.

From one day to the next we bought the ticket and got the plane. We wanted first of all to see what Brazil really looked like! We had learnt to speak Portuguese properly. If you don’t speak a language here’s barely nothing you can do. That was the problem in Africa. If you can’t speak a country’s language there is always distance between you and the people.

One evening we were in a favela. Hubert Fichte said, when we hear drumming the first thing we should do is stand still, then follow the drum rhythms. We heard the drums and came to a halt in front of a hut. We had been standing there for barely five minutes when a woman came out and started talking to us in Portuguese.

And then we told her what we wanted and who we were, and she replied: “Come in!”

It was so impressive how deeply immersed they were in this ritual. For them, nothing else mattered other than the gods, the dances and the chants. I was totally entranced! I could barely contain myself. I still can’t, even now, when I describe it.

Candomblé, this rite. It’s everywhere in Brazil, even in the south in Sao Paulo. But the classical place for it is Salvador in Bahia. And that’s where we then went to.

I am not really afraid of dangers because people always exaggerate them.

Only once, in Rio, I was stopped on the street and told, “You shouldn’t be walking around here on your own”. And I asked, “Why not?”

“It’s too dangerous!” And then I told them that I take photographs. “Then we’ll accompany you!” I thought, “Oh God!” So they then kept following me around. I wasn’t at all happy about that.

Untitled (Leonore Mau on her 90th birthday), 2005

© Nathalie David

Ohne Titel (Portrait of Leonore Mau), 2007

© Nathalie David