Portrayed and companions remember Leonore Mau

Nathalie David a filmmaker and artist, was Leonore Mau’s long term personal assistant.

In 2016 after finishing her film Diese Photographin heißt Leonore Mau, (52 min, DE 2005 – 2016 https://vimeo.com/223781321), she began to record a series of conversations with people from Leonore Mau’s environment and those who were photographed by her.

You can read five excerpts from these conversations, as well as an excerpt from Leonore Maus’ last interview (2006) below: To the interview with Ingo Niemann

Susanne Amatosero at home on Hamburg (6 January 2016)

How I first got to know Leonore Mau? I was in the Caribbean at the time and got to know this priestess from the Spiritual Baptist Church. She then invited me to the church. The priest had been preaching to the congregation and then added, “As everyone knows, we once had guests here from Germany before, Hubert Fichte and Leonore Mau.” He took the two books Xango and Petersilie out from below the altar and we all perused them together. He then gave me presents to pass on to Hubert Fichte. Two years later we returned with the presents for Hubert Fichte. I called Leonore Mau, but she fobbed us off. That was precisely the time when Hubert Fichte was dying.

I wouldn’t have pursued this any further, but our sound technician insisted. At some point, the two of us were invited to dinner at Leonore’s. At that time, Leonore was already over sixty, yet she had stayed very young. She was very elegant and mindful of social graces, but she wasn’t haughty. I found talking to her extremely engaging. She was a generous woman. Her generosity also had something to do with education. In the sense of the word “polyglot”, that you are connected with the entire world through your education, your background and your self-awareness, and for this reason you have no need to be petty.

We didn’t talk much about theory. Instead, Leonore Mau told more graphic accounts about how one or another photo came about, about how she came to participate in a certain ceremony and how poor the light was there, or how someone had stolen her camera.

Her stories were about Hubert Fichte, about the people there and about their amazing experiences. Basically, about the poetic nature of this otherness, this unexpectedness and also about the beauty of the people there.

Leonore’s photos are colourful. Yes, she shot in black and white, yet I believe colour actually played an important role for her, the warm colours she always worked with. In fact, her pictures have something epic about them. Effectively, they are not snapshots. They don’t just say something about a single moment but also about something that recurs. If an animal is sacrificed in a ceremony and you see the blood seeping from it, you don’t think, “There’s an animal being slaughtered”. Instead, you know you are looking at an image of an event that is ritually staged over and over again. Something epic, or even classical. She and Hubert Fichte researched these ceremonies: they’re weren’t just there for an evening but went back repeatedly. Also, the people play less of a role as individuals than as protagonists of their professions or their history. When I say, for instance, that these old ladies from the Casa das Minas are “protagonists of their history” I mean that there is also a resonance of the fact that their ancestors arrived there as slaves. All this history spawns the epic dimension of these images.

Leonore Mau did not stage her photographs. She knew exactly what mattered in these ceremonies. She waited as long as it took until whatever it was that she wanted to see took place.

Leonore Mau never took sensationalist shots. And she didn’t ever photograph someone such that you get the feeling that in that moment the person was reluctant to be photographed. When you look at her portraits she took of people it is instantly clear that she did so with their consent.

As a medium, photography is very close to theft, but she never stole her pictures. She was also someone who people put trust in more than not. She never looked down on anyone. Rather, she would have looked for some hidden meaning that maybe she couldn’t grasp at first. She treated the people she met very attentively. She placed great value on understanding other languages. She and Hubert Fichte learned ancient Greek together in order to read in the original. Portuguese of course, English, French and Creole as well.

To put it poetically, she was simply also a world citizen. Her flat was wonderful too. What I loved most were all the delightful things she had brought back from her travels. Of course, the flat was enormous, with a fantastic layout, very stylishly furnished, yet with a great simplicity, not crammed full of stuff. Everything that had been Hubert Fichte’s she treated with very high regard. Like everything that Hubert Fichte had done was wonderful. She enthused about him to me. In this respect then she was also the classical “woman at his side”. Regardless: theirs was an amazing, extraordinary encounter. Given her whole story, she struck me as a very special woman. The decisions she made were not in any manner typical for her generation.

She had in fact studied set design and had intended to work as a stage designer, but then she became pregnant from this man who was twenty years her senior. You could say that because she was suddenly a married woman and mother she had actually lost part of her youth. But in the late sixties she managed to reclaim this for herself. And Hubert Fichte was per se someone who would venture into any milieus or parallel worlds for the purposes of research and opening them up or reporting on them. No matter whether it was the “Palette” or a psychiatric hospital in Benin.

One got the feeling that she had a very fulfilled life. She never ever complained, not even about her ailments or frailties as an old lady.

Untitled (Susanne Amatosero), 2000

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (Hubert Fichte at the 106-year-old

King of Abomey), 1975

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (Priestesses of the temple Casa das Minas), 1981/82

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Figures in the shared flat of Leonore Mau

and Hubert Fichte in Dürerstraße in Hamburg-Othmarschen

© Nathalie David

Bookshelf in the shared flat of Leonore Mau

and Hubert Fichte in Dürerstraße in Hamburg-Othmarschen

© Nathalie David

Untitled (Leonore Mau with husband and son), around 1950

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

F. C. Gundlach in Hamburg (8 April 2016)

When I got to know Leonore she was a photographer.

I had been running a postproduction agency for a while. We developed the films that they couldn’t while they were on their travels. That’s how we got talking. When she came to collect her pictures she showed them to me and we discussed them.

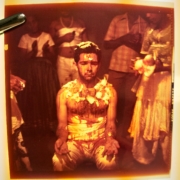

In 1977 I founded a gallery. One of the first exhibitions we did was about African-American religions. Of course that was very unusual. Then I went to see her in Dürerstrasse. We looked through her photographs and selected material for the exhibition. I made the prints in my own lab and then gave them all to her as a gift. They were done on Cibachrome. We had one print of a Candomblé. It showed a bleeding man who was seated. It used to hang at the back of the gallery, as large as the wall. Fichte once held a reading there. Then we decided to do a portfolio. We published several portfolios, each one with ten motifs on a specific theme or related to a biography. We hit on the name Grosse Anatomie . In Bahia Leonore had photographed a human body being dissected, something that happens all the time there. In the pictures you can see a crowd of children next to the operating room watching what is going on. We produced twelve copies: she was given six, I got six. Fichte then also wrote a text about it.

As far as I know, she mostly photographed with a 35mm camera, but also 6×6. But I think her most important camera was her compact camera because it also enabled her to photograph in very difficult situations that required discretion and where one would rather be inconspicuous.

This couple – the lanky, thin beanpole, one might say, but with a huge head, accompanied by a woman with white hair – had of course a presence about them, sensational. Naturally, he assumed the leading role. He was a world champion scrounger. They flew by Concorde – he fixed that. But maybe that was what was good about her role, that she remained passive and, as it were, voluntarily “flew” in his shadow. People were then busy with something else.

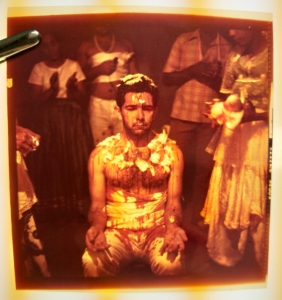

She and Hubert Fichte were accepted as a couple. They weren’t viewed as voyeurs but were taken seriously and incorporated into the ritual. When you photograph with a Leica you have the camera directly against your eye, so you get, as it were, the same perspective as your own eye. And it is the quietest camera there is. It’s possible they didn’t even notice that someone was also taking photographs. What is highly unusual is that while they were in San Salvador in Bahia they succeeded in going to a Macumba and all kinds of things. On all the many trips they made Leonore was always a very alert observer. The way she perceived each country they visited is reflected in her pictures. She perceived things as an observer, then photographed them. Under all kinds of conditions, because often there was very little light. But she still did her thing as a photographer. In South America there were no labs that developed slide films. They brought them back and we developed them in our own lab.

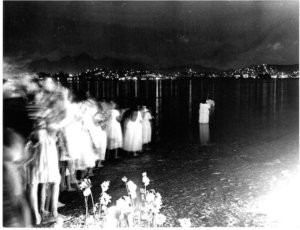

She took a lot of portraits. She used the opportunity when Fichte was giving an interview. When conversation got going she was every ready and portrayed all kinds of people who were being interviewed. Like Genet, for example. There’s a whole series of shots. I think she only rarely used a flash. She made do with the light that was around the people. She didn’t want to be noticed, that was the crucial thing. And the spontaneity she had while photographing.

The Pina Bausch photos were probably the last big task she set herself. They both knew each other well, which, given there were no barriers, allowed her to work freely. They also had a good personal rapport. She developed a very personal style for approaching people without somehow intimidating them. They kept their openness, stayed true to who they were. That is crucial. They didn’t pose. They also trusted that they wouldn’t be shown up. Because dancers are hard to photograph. Their art is about expressing themselves through the movements of their bodies. But this situation was completely the opposite. In a static situation she took large amounts of full-figure shots, she kept her distance. It seldom happened that someone would look directly into the camera. The photos she took were always very spontaneous.

Leonore Mau came quite late to the camera and the camera was simply her instrument.

Untitled (The bloodbath), 1971

Colour slide 6×6

© Marlene Burmeister

Untitled (Candomblé ceremony at night), 1969

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (Jean Genet), 1975

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

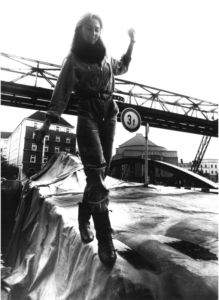

Barmen. Brücke am Opernhaus, 1987

(with the French dancer Helena Pikon)

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Ulrike Ottinger at home (9 May 2018)

It was during the time I was in Paris, for sure. I think I first became aware of her through her photographs and only then did I get to know her. Only once we really started talking intensely, that was then in Berlin and Hamburg. She had an exhibition here in Berlin. Somewhere around the Hackesche Höfe there was a lovely bookshop and that’s where Leonore had an excellent exhibition. She had also been here on a previous occasion, probably at the Akademie der Künste.

When we spoke we talked about our various trips. I know that I once confessed to her that I sometimes find it really embarrassing to point my camera at people, but that with time I’ve learned to stop trying to be discreet about it and to do it completely forthrightly. In other words, to smile at someone and nod to them, so to do it quite blatantly. So I asked her if she also had this issue. She said yes, it often takes quite an effort.

She also has something I feel quite an affinity to, yes, a kind of “way of approaching” things I feel altogether familiar with. She told me that this is an experience you have – one, by the way, I also had – when you are a lot younger and much more brazen, but that this is compensated for later by the experience you gain in dealing with people. We discussed this sometimes, this situation and also one’s inner conflict in needing to overcome yourself to do something, as a certain kind of timidity. And sometimes you wonder if that’s being indiscreet, whether in a ritual or in everyday life.

I remember she happened to be in an exhibition we were visiting together in this gallery – actually more of a bookshop – and was standing in front of her photos, and that she then started telling me a bit about the conditions and background situation, and other things that were going on there. We never actually talked about technical stuff and so on. At least I don’t think we did, even though something like that might have been quickly mentioned, not en passant, but we were both not exactly, like people say, “tekkies”, just simply more interested in content and how you photograph something to make it recognisable.

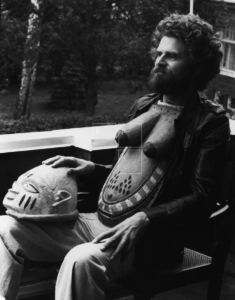

There is one photo she took of Hubert Fichte that I think is fantastic. It’s the one where he has this body mask with a woman’s breasts, and if I properly remember […] he is sitting like one of those mighty Congolese kings and is also, I think, holding a head mask on his knee, on which he has placed his hand. For me this is a brilliant portrait of Fichte because it manifests all the ambivalences about him and is simply a brilliant picture in its overall composition, right?

I think they [Leonore Mau and Hubert Fichte] gave each other a kind of stability and security that you need if you choose to live differently, not so couched in regular routines, in a bourgeois, settled order. She possessed an openness, derived maybe from her upper-class attitude, and she was also able to disregard certain things. […]

For her, aesthetics were a matter of course and I think she was very sure of herself when it came to choosing the exact framing she wanted at a certain moment. This is very clear to see: I’m familiar with a lot of her photos taken in very different situations, things where you have to work very quickly, such as during the rituals. Documentary stuff, where you really have to make split-second decisions. Just like in the composed shots or in that portrait of Hubert Fichte.

Her photography really gets close to things, yet at the same time she caught the essence of things as well as maintaining a precise observation of everyday life. But what I particularly meant is the playful dimension, even in the interaction of both aspects. I consider this absolutely crucial.

In my view, her photos are some of the best I know when it comes to rituals, and that is only something you can do if you have an understanding of them, if you are familiar with them. If you aren’t, you can’t photograph them. Indeed, that is evident in her photographs, and of course that was also present in her exchange with Fichte and with people in general. If you spend a lot of time in another country, after a while you start belonging to the place a bit. I think you will always remain “the other”, but nonetheless you have then become anchored as “the other” in that culture and have found a role to play, and for people there you also sort of belong to the place.

And for her, that was a matter of course, so then it seems natural and not so laboured and contrived – just kind of right. It is simply “right”. Yes, she had courage.

There are things that are full of contradictions. And she and Fichte dared to expose themselves to these. The things they published, whether in photography or text, had a huge impact at the time, back in the sixties and seventies, without question.

Untitled (Creditor in a trance), 1972-1978

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (Hubert Fichte with belly mask and

clay head mask of the Gelede), 1979-1983

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

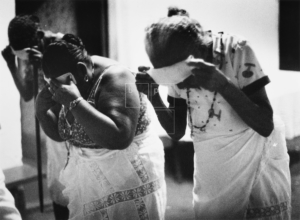

Untitled (Priestesses of the temple Casa das Minas), 1981/82

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Untitled (First exit of the novices), 1971

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Yoko Tawada at home on Berlin (22 March 2016)

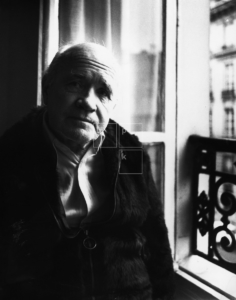

I don’t know how it [our first encounter] came about. My recollection is not necessarily right. My publisher Claudia Gehrke and I visited Leonore Mau two or three times, independently of this assignment. I remember that I was quite unaware that I was supposed to be being photographed. I was happy to be visiting her, but was then suddenly informed she’d be taking pictures of me. But there was much less commotion involved than with other photographers. With Leonore it wasn’t like that at all. It was very calm. I recall the room being rather dark, without the lighting you’d normally get in a photo studio, and Leonore Mau asked me where I’d like to put myself, at the window perhaps? I went over and stood there, after which there were no more instructions: I just stood there and didn’t even have the feeling I was being photographed because Leonore Mau was completely quiet. She moved as if performing Noh theatre, where actors just slip across the floor. She must have moved somehow, she changed her position after all, but I didn’t notice. That’s why I was so astonished when I later saw the photos she’d taken. She was certainly not dogmatic. She never told me to push my hair to the back or anywhere else, that also happened by chance. […] It seemed a short time to me. Maybe because it was pleasant. Time is a subjective thing. I don‘t know how long it lasted, hard to say, but it was certainly not long. […] As if she was just trying out taking some photos by the by, that’s how it felt. And I didn’t even notice that they were supposed to be portraits, which turned out to be really lovely. But, as I see it, it’s not a typical portrait of a writer, more like a painting.

I remember that she really enjoyed having visitors, even people like me who she barely knew. My publisher knew her much better. The way she welcomed us, calmly but very warmly, no big hugs and cheek-kissing or grand words. And then she took pleasure in putting wine on the table, everything was so quiet and natural. Leonore Mau was almost a kind of place where you could meet without ulterior purpose, without compulsion, without complications.

Much later I was doing a theatre project with Ulrike Ottinger. She was showing her films in Hamburg and all her Hamburg friends were there, including Leonore Mau too. By then she was already a little unsteady on her feet. I didn’t know that the two of them were friends, and then I thought, well, obviously, they have so much in common in their work, their interest in rituals and shamanism and photographs. A certain way of being very careful in how they deal with people, patiently studying rituals for quite long periods before taking photos. Rather than saying, now do this or that, or adopt this pose, and then photographing the result. But simply sticking with it for as long as it takes before everyone forgets she’s there – and then to start photographing.

Untitled (Yōko Tawada)

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

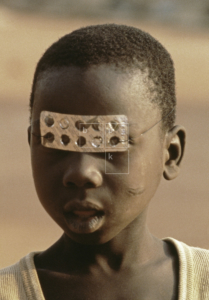

Untitled (Boy with blister mask), 1975

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Wolfgang von Wangenheim in Hamburg in the Hotel Atlantic (4 February 2016)

I became acquainted with Leonore Mau early in 1976. It was my last year in Dakar where I had been working as an editor for German and trained French German teachers at the university. I had got to know Hubert Fichte two years earlier when he came with Leonore Mau to Dakar to do research and describe the conditions in the psychiatric clinic in Fann, which was directly adjacent to the university on the Dakar peninsular. It transpired that in 1976 I was able to let Hubert and Leonore use one of the two flats I had in Dakar, the one I rented from the university. That’s where I got to know them both. And after period they spent there – it must have been two or three months – all of us, Hubert, Leonore, Amadou, my Senegalese partner) and I, then drove to Casamance in order to visit a “psychiatric village”.

Hubert had been in touch with the French director, a psychiatrist by profession, and asked how the Senegalese traditionally healed or treated mental illnesses and psychiatric disorders, and how he sought to integrate this approach into a method that combined traditional and modern methods of treatment both in Dakar and in that village in the south of the country.

We drove down to the south of Senegal, to the region known as the Casamance. There, not far from the capital Ziguinchor, an already existing village had been furnished with a health care service. In the village were many mentally disturbed and socially conspicuous people, people who were lightly shackled with a tree stump tied to their legs – which Leonore then photographed and Hubert described. It was in this village we visited that I also photographed Leonore while she was taking photographs. As it happened, the two of them had been to the place once before, so people were already familiar with them. That, in fact, was their method: Leonore never photographed strangers anywhere, so when she began to photograph someone it was always someone who knew that it was her, not on the first day, but on the second or third, at some point or another, quite casually. That is how she was able to take so many spontaneous shots that reveal moments of such intimate enthusiasm, especially in situations to do with healing or baptism in the river or such like. Intimate gestures made by sick patients or healthy people, Leonore Mau patiently captured these moments just as they happened. And the people making them didn’t notice or it didn’t bother them that a woman was also there taking a few photos.

Untitled (Leonore Mau in the psychiatric village

„Village Émile Badiane“ of Kenya near Ziguinchor,

in the Casamance, Senegal), 1976

© Wolfgang von Wangenheim

Untitled (Hubert Fichte in the psychiatric village

„Village Émile Badiane“), 1976

© Wolfgang von Wangenheim