Leonore Mau and Hubert Fichte

Mau – Fichte // Irma – Jäcki. Photographer and writer

Christa Karpenstein-Eßbach (2022)

Irma and Jaecki, Leonore Mau and Hubert Fichte – the first two are literary inventions in Fichte’s seventeen-volume Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit (The History of Sensibility), the second pair were people in blood and flesh. Fictional or otherwise, one is a photographer, the other a writer. What they share is that they are bound together in love and work, that the two art forms, writing and photography, are interwoven and that the one is mirrored in the other whenever they take their instruments on their travels to explore and depict the worlds of other cultures.

“You want to know everything about me. / I want to know everything about you”[1]

In the novel Forschungsbericht (Research report), Irma is asked by Jaecki, “Does it bother you that you will be featured in it?”[2] It bothered the semi-fictional Irma/Leonore just as little as it did the real Leonore Mau.[3] In Hotel Garni, the opening volume of the Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit, those who want to know everything about each other (which, incidentally, is a reply to the preceding question, “What do you mean by love?”) make their first appearance. Here there is no narrator directing his protagonists from an elevated, supreme position, instead a reciprocal relationship of reporting in the manner of a two-way interview. While elsewhere, in the context of his probing ethnological explorations in other countries, Jäcki/Fichte adopts the stance of a dissociated interviewer, here he also allows himself to be the interviewed subject, suggesting that the practice of “wanting to know”, of pursuing precise perception and observation that will be intrinsic to their later shared travels to the worlds of other cultures, is now being mutually put to the test in the intimacy of loving coupledom.

The common themes are personal and family history, childhood and puberty, intellectual interests, the atmospheres of the post-war period, sexuality on repeated occasions with all the variants of erotic desire and all manner of passions and aversions, and the paths that drew one of them towards photography and the other to writing. The way they speak is neither confessional nor taboo-breaking. Rather, it proceeds with the cool objectivity of a report documenting exteriorised intimacy. In the process, the precision that matters most in all things can at times assume comic dimensions, such as when Irma, on answering Jäcki’s question, “So what is it you like about a man’s arse?”, in turn poses him a question: “When naked or in trousers? / Because that’s a huge difference. / If you see it in trousers it is simply a voluptuous shape. / But when it’s naked, you see a whole lot more.”[4]

As if Irma and Jaecki were trying to follow Freud’s old adage that love and work are the two base materials for a successful life, both of them repeatedly recount how their photography or their writing began. Jaecki wants to turn his back on the prevailing mood in post-war German literature, while Irma, trained as a set designer, begins increasingly to use her camera as a means of leaving the world of Hamburg. A two-pronged verbal action lends expression to their common goal when Jaecki says, “I wanted to see the world”, and Irma, “I had the idea to travel around the world with a camera”.[5]

“You are making a great poet of me. / I am making a great photographer of you.”[6]

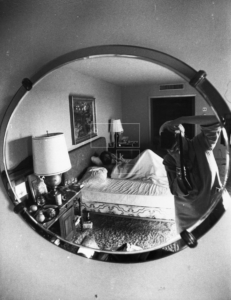

One aspect of the relationship between the photographer and the author was their examination of the singularities of both art forms, a dialogue that was never free of tensions and rivalry. With unbounded enthusiasm the author proposes: “‘All I would ever photograph is white eggs,’ Jaecki rhapsodised, ‘against a white limestone wall’”.[7] What Leonore Mau made of this absurd suggestion to eschew the essential property of photography, the play with light and contrasts, can be seen in her Selbstportrait mit Ei um ein Uhr nachts am 3.10.1967 (Self-portrait with egg at one o’clock in the morning on 3 October 1967).[8]

For a start, the modes of production of images or writing could hardly be more different. A photograph is made in the instantaneousness of a moment, here and now, as the author tells us, not without envy: “Total. Click. Done. The whole story in a thousandth of a second. The world as pure image. That is true art. Nothing more than a camera.”[9] Writing, on the other hand, is discontinuous, constantly interrupted and corrected by reflection or revised compositional strategies. And even when it is just a question of relating three long gone seconds, the writer, Jaecki explains, might need as much as an entire novel for their description. He has to deal with the “falling apart of all times within a single moment”.[10] Yet anyone who has ever shouldered photographic equipment and works with more than just pen and paper will know that this “nothing more than a camera” does not come even remotely without preconditions. Choosing one’s vantage point and framing, aperture and lens, determines the technical and processual instrumentalization of the gaze, and this is a complicated matter. Which is why taking a photograph can also fail at the given moment. As the author, who places store by the duration of writing, freely admits, he will “never become a photographer”, while the photographer has “no time for white eggs” – the “ideas of an author who is describing a photographer”.[11]

One thing is beyond the capacity of photography: it cannot represent the layers of time, time that is lost and regained in memory, or connect the here and now with there and then. To do this requires language with which former time can be inducted into the present moment, or can elicit former time from the now. However successful one of Irma’s photos of a site of remembrance from the past, like Jaecki’s beloved allotment in Hamburg’s Lokstedt neighbourhood, might seem in itself, it is nonetheless impossible to discover in it all those layers of time and traces of memory that mattered to Jaecki.

But the silence of the images harbours a great asset vis-à-vis the limitations of language. As Siegfried Kracauer observed, it is photographic images that first lend visibility to what is elementary and common to people. Images are far more easily decipherable, spontaneously accessible and possess no boundaries to their reception. The author writes in a language that first has to be translated for people from other countries if what he is writing is to be counted as world literature in the eminent sense. In comparison with photography, Jaecki realises that “an author never has success like this. I had always hoped that Africans would one day read me with the same enthusiasm.”[12] When Leonore Mau exhibits her photos in Harlem, Irma actually becomes “Black”, and all the competing author can do is to ascertain that “I, however, am entirely Black – only no one can see it.”[13]

“…that you go to a foreign country…”[14]

The numerous journeys undertaken by Fichte and Mau not only took them into the unknown but also into uncertainty. Instead of travels that suggest holidays or tourism, one should call them expeditions that are marked by contingencies, that can fail or succeed because the conditions for exploring and seeking are not fully under the sovereign control of the explorer. In Explosion, the account of the three trips to Brazil, we read: “In somewhat of a panic Jaecki whisks Irma away / What’s going on: / Come on. / Look for Candomblés / Where / We’ll take a taxi and drive to Capelinha und look for Candomblés / How? / Just like that. Ethnology is like pederasty: you have to go a long way on foot. / (…) And why Capelinha. / Because the name is so pretty.”[15] To find the places and people that inspire interest no travel guide will help, but what certainly will is to keep your ears on the sound of drums or your eyes on the sky where circling vultures might point the way to the favela.[16] If the “sacrifice was missed”, the “procession rained off” or the “investigation failed”[17], if information proved dubious or photography difficult, inquiries will resume all over again the following day.

They researched two realms. First, the rites of African-American religions, cult practices with their sacrificial rituals, states of trance and rapture, Dionysian exaltation and transgressions that barely have any relation to notions of a calming space of sanctity. In Xango and Petersilie, the four volumes about African-American religions, the photographic and written testimonies converge. They went in search of practices and sites of extraordinary experience, of more or less confined zones of recurrent exceptional circumstances. Among these also count madness and psychiatry. Besides all that is extraordinary is the entire realm of what is ordinary, of everyday life, of habits, of that which can be heard and seen in the streets and squares of towns and villages, people’s gestures, expressions of joy or sorrow – observed, photographed, described.

In neither Mau’s nor Fichte’s case does travelling to foreign countries result in a depiction of compact cultures, let alone something like ethnologically underpinned “identity”. Mau considered herself explicitly “not an ethnographic photographer”[18], while Fichte subjected the prevailing ethnology of his time to acrid criticism. Ethnology is relegated to an anthropology reminiscent of the age of Enlightenment based upon a phenomenology of the plethora of human behavioural patterns, rather than distinguishing some compact Other. The children of Herodotus – as cited in the title of the book, Die Kinder Herodots, edited by Ronald Kay, which describes the renowned explorer of antiquity and assembles photos by Leonore Mau and texts by Hubert Fichte – are uniquitous.

Literature

Braun, Peter, Die doppelte Dokumentation. Fotografie und Literatur im Werk von Leonore Mau und Hubert Fichte, Stuttgart (Verlag für Wissenschaft und Forschung) 1997.

Karpenstein-Eßbach, Christa, Fotografie und Schriftstellerei, in: Das Gewicht der Welt und das Leben in der Literatur. Zum Werk Hubert Fichtes, Göttingen (Wallstein) 2022, S. 165-186.

Kay, Ronald; Leonore Mau, Hubert Fichte. Die Kinder Herodots, Frankfurt a. M. (S. Fischer) 2006.

Schoeller, Wilfried F., Hubert Fichte und Leonore Mau: der Schriftsteller und die Fotografin, Frankfurt a. M. (S. Fischer) 2005.

Footnotes

[1] Hubert Fichte, Hotel Garni. Die Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit Bd. 1, Frankfurt a. M. (S. Fischer) 1987, S. 148.

[2] Hubert Fichte, Forschungsbericht. Die Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit Bd. 15, Frankfurt a. M. (S. Fischer) 1989, S. 141.

[3] Interview mit Ingo Niermann

[4] Hubert Fichte, Hotel Garni, S. 16.

[5] Hubert Fichte, Hotel Garni, S. 10, 144.

[6] Hubert Fichte, Der Kleine Hauptbahnhof oder Lob des Strichs. Die Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit Bd. 2, Frankfurt a. M. (S. Fischer) 1988, S. 68.

[7] Hubert Fichte, Eine glückliche Liebe. Die Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit Bd. 4, Frankfurt a. M. (S. Fischer) 1988, S. 25.

[8] Siehe Ohne Titel (Leonore Mau mit Ei und Rolleiflex-Kamera vor dem Spiegel)

[9] Hubert Fichte, Eine glückliche Liebe, S. 28.

[10] Hubert Fichte, Der Kleine Hauptbahnhof, S. 198.

[11] Hubert Fichte, Eine glückliche Liebe, S. 27 ff.

[12] Hubert Fichte, Forschungsbericht, S. 129.

[13] Hubert Fichte, Der Kleine Hauptbahnhof, S. 69.

[14] Hubert Fichte, Hotel Garni, S. 144.

[15] Hubert Fichte, Explosion. Roman der Ethnologie. Die Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit Bd. 7, Frankfurt a. M. (S. Fischer) 1993, S. 142.

[16] Hubert Fichte, Explosion, S. 54.

[17] Hubert Fichte, Forschungsbericht, S. 127, 137.

[18] So im Interview mit Ingo Niermann (S. 4, LINK?)

Untitled (Self-portrait with a portrait photo

by Hubert Fichte), 1962

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

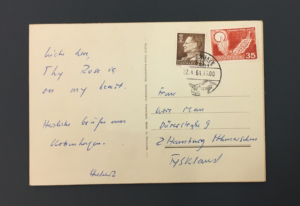

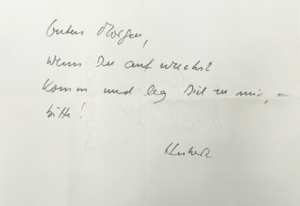

Postcard from Hubert Fichte to Leonore Mau, 1964

© Nathalie David

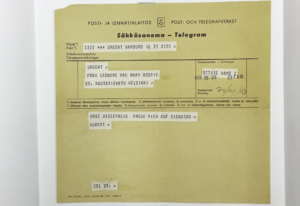

Telegram from Hubert Fichte to Leonore Mau, 1965

© Nathalie David

Untitled (Leonore Mau with egg and

Rolleiflex camera in front of the mirror), 1967

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

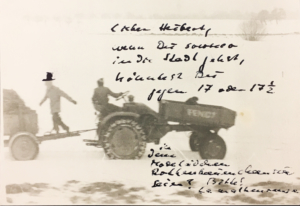

Message from Leonore Mau to Hubert Fichte

© Nathalie David

Ohne Titel (Self-portrait in the hotel room), 1977/78

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

Message from Hubert Fichte to Leonore Mau

© Nathalie David

Ohne Titel (Leonore Mau and Hubert Fichte), 1975

© bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

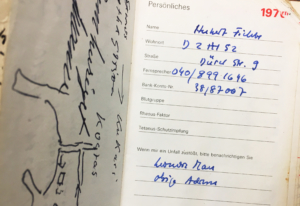

Pocket diary of Hubert Fichte, 1976

© Nathalie David